Martin Van Buren had a plan. The year was 1824, and Van Buren was disgusted by the corruption that had soaked through the Republican party. The Federalist party had long since ceased to be, and politics in the United States had become a one-party game; as such, with no competition to keep it in check, that one party became a magnet for every type of disreputable political behavior. Having soundly defeated Hamilton’s Federalists, the Republicans then went on to become what they beheld, adopting all the old Hamiltonian policies they had once stood against: protectionist tariffs, internal improvement spending, foreign adventurism, ballooning central government, and even that most hated of institutions, the central bank. Aided and abetted by a life-tenured federal judiciary that had long been usurping powers never given to it by the Constitution, it seemed as though the permanent enshrinement of the Hamiltonian system was a foregone conclusion.

But Martin Van Buren had a plan. If there existed no opposition party to oppose the slide into tyranny and corruption, he would create one. Having long been possessed by that quintessentially American spirit of fundamental — if somewhat inchoate — distrust of centralized political power, he traveled to Monticello to meet with the man who he believed, more than anyone else, was capable of helping him refine his ideas into a viable political platform: Thomas Jefferson. Van Buren emerged from that meeting energized, and, ever more convinced that the vestiges of the Federalist party were rapidly dominating the Republicans, assured the former president that

you are not sensible my dear Sir, of half the respect, the reverence, & warm affection, entertained for you by all the old and uncorrupted Republicans. and notwithstanding the late rewards for apostasy, you may rest assured, that the number of those is yet larger Sufficiently So, I hope, to rescue their cause from ruin & their country from misrule.

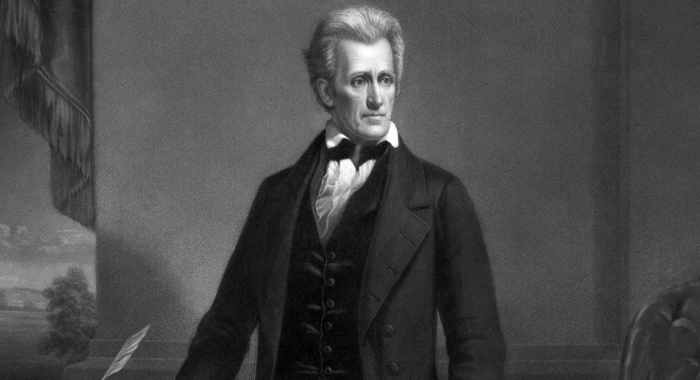

Martin Van Buren had a plan, he had a cause, and he had a body of support. All he needed was a charismatic front man to tie the whole package together; someone tall, stately, and respected, ideally a war hero — a new George Washington, to be the figurehead of Van Buren’s new, reborn America. He found exactly what he was looking for in the fiery but unsophisticated Andrew Jackson.

The election of 1824 was the high-water mark of the corruption rampant in the so-called "Era of Good Feelings." Four men were in the running for the presidency, all nominally on the Republican ticket (as there was no other party): senator Andrew Jackson, secretary of state John Quincy Adams, secretary of the treasury William Crawford, and speaker of the house Henry Clay. With the electorate so sharply divided, none of the four obtained a majority of the electoral vote; with 131 votes needed to win, Jackson’s 99 was the closest total — a plurality, but not the majority the Constitution requires. The Twelfth Amendment explains what happens in that case:

The person having the greatest Number of votes for President, shall be the President, if such number be a majority of the whole number of Electors appointed; and if no person have such majority, then from the persons having the highest numbers not exceeding three on the list of those voted for as President, the House of Representatives shall choose immediately, by ballot, the President.

In accordance with the Twelfth Amendment, the election of 1824 was handed off to the house to decide, but not before the weakest of the four candidates was culled: Henry Clay — the speaker of the house. While on the one hand assuring that Clay would not become president, this peculiar situation also vested in him the power to play kingmaker; as speaker, he held considerable influence over the house, and it was (rightfully) believed that he would be able to hand the presidency to whichever of the men he so chose. Jackson, who won a plurality of both the popular and electoral votes, was confident that he would be the next president, and was stunned when Clay — who hated Jackson — handed the office to John Quincy Adams instead. Rumors flew that Clay and Adams had struck a "corrupt bargain" according to which Clay would give Adams the presidency in return for an appointment as secretary of state; these rumors were not quelled in the least when Adams did indeed so appoint Henry Clay. These allegations were never proven (and, even if they were, it’s not clear that anything could be done; patronage was an old established Hamiltonian principle, and nothing exists in the law that would prohibit exactly such a "bargain" being struck), but they lit a fire under Old Hickory, driving him directly into Martin Van Buren’s waiting arms, where he agreed to be the point man for Van Buren’s new Democratic party. Jackson and Van Buren never forgot or forgave the corrupt bargain, hammering on it relentlessly for the next four years, culminating in the election of 1828, after which Jackson exhorted the congress:

I consider it one of the most urgent of my duties to bring to your attention the propriety of amending that part of the Constitution which relates to the election of President and Vice-President. Our system of government was by its framers deemed an experiment, and they therefore consistently provided a mode of remedying its defects.

To the people belongs the right of electing their Chief Magistrate; it was never designed that their choice should in any case be defeated, either by the intervention of electoral colleges or by the agency confided, under certain contingencies, to the House of Representatives.

In 1828, Jackson again faced John Quincy Adams, crushing him handily with the support of Van Buren’s political machinery, and ushering in what would be called, if American political historians were a bit more honest, the third American republic. It is a bit ironic that the corrupt bargain was the catalyst for the formation of the Democratic party, since, under Jackson’s rule, the so-called "spoils system" would be fully introduced. The spoils system was nothing more or less than a widespread system of political patronage, whereby supporters would be rewarded by the victorious president with cushy government jobs and favors — nothing more or less than the exact thing Adams and Clay allegedly did that so incensed Jackson. Historians often pretend that the spoils system died with president Garfield in 1881, but this is a lie; in reality, it is still very much a feature of American politics, but instead of supporters being rewarded with postmasterships and customs house postings, they’re nowadays given cabinet posts, ambassadorships, and lucrative government "contracts."

Easily the thing president Jackson is best remembered for is his opposition to the Second Bank of the United States. Many libertarians, indeed, will go so far as to praise Jackson’s handling of the bank — after all, libertarians are against central banking, and nothing’s more anti-central banking than eliminating the central bank, right? Well, the devil, as always, lurks in the details, and this devil in particular is no slouch. Andrew Jackson is often incorrectly portrayed as some type of principled, proto-Ron Paulian enemy of central banking, but this is simply not the case. As president Jackson himself said in his first annual message on 8 December 1829:

Under these circumstances, if such an institution is deemed essential to the fiscal operations of the Government, I submit to the wisdom of the Legislature whether a national one, founded upon the credit of the Government and its revenues, might not be devised which would avoid all constitutional difficulties and at the same time secure all the advantages to the Government and country that were expected to result from the present bank.

Clearly, Jackson was no opponent of central banking in general; he just didn’t like this bank in particular. What was his objection to it? The reality of the situation is that Jackson believed (correctly) that the national bank system was a supporter of his political opponents — the bank’s director, Nicholas Biddle, was a close associate and crony of Jackson’s arch-enemy, Henry Clay — and he fought his famous "war" against it for purely partisan political reasons.

The Second Bank of the United States had been created in 1816, and was chartered for twenty years. As such, it wasn’t due for a rechartering until 1836. Henry Clay, however, saw an opportunity to use the bank as a weapon against president Jackson, and approached Biddle in 1832 to suggest that he apply to congress for a new charter four years early. 1832 was, of course, an election year, and that was the crux of Clay’s plan; as he saw it, Jackson would be placed in an unnavigable trap: he would either sign the charter (thus sacrificing his opportunity to modify the bank to be more Democrat-friendly), or else he would veto the charter, lose popularity, and go down in defeat in the election, after which the new president (Henry Clay himself, of course) would recharter the bank anyway. It seemed like a perfect snare, but Henry Clay had failed to account for president Jackson’s resourcefulness. Jackson opted to veto the recharter, but, instead of just issuing a veto statement containing a dry missive on the Constitution (which the Republicans could use as easy ammunition in the election), he did an end-run around them, pointing out in his own veto statement that the Supreme Court, in the case of McCulloch v. Maryland, had already declared the bank to be Constitutional. How did Jackson reconcile this tension? By rejecting both Marbury v. Madison and the principle of stare decisis:

It is maintained by the advocates of the bank that its constitutionality in all its features ought to be considered as settled by precedent and by the decision of the Supreme Court. To this conclusion I can not assent. Mere precedent is a dangerous source of authority, and should not be regarded as deciding questions of constitutional power except where the acquiescence of the people and the States can be considered as well settled. So far from this being the case on this subject, an argument against the bank might be based on precedent. One Congress, in 1791, decided in favor of a bank; another, in 1811, decided against it. One Congress, in 1815, decided against a bank; another, in 1816, decided in its favor. Prior to the present Congress, therefore, the precedents drawn from that source were equal. If we resort to the States, the expressions of legislative, judicial, and executive opinions against the bank have been probably to those in its favor as 4 to 1. There is nothing in precedent, therefore, which, if its authority were admitted, ought to weigh in favor of the act before me.

If the opinion of the Supreme Court covered the whole ground of this act, it ought not to control the coordinate authorities of this Government. The Congress, the Executive, and the Court must each for itself be guided by its own opinion of the Constitution. Each public officer who takes an oath to support the Constitution swears that he will support it as he understands it, and not as it is understood by others. It is as much the duty of the House of Representatives, of the Senate, and of the President to decide upon the constitutionality of any bill or resolution which may be presented to them for passage or approval as it is of the supreme judges when it may be brought before them for judicial decision. The opinion of the judges has no more authority over Congress than the opinion of Congress has over the judges, and on that point the President is independent of both. The authority of the Supreme Court must not, therefore, be permitted to control the Congress or the Executive when acting in their legislative capacities, but to have only such influence as the force of their reasoning may deserve.

One can certainly understand the willingness of people to accept the apocryphal quote "John Marshall has made his decision, now let him enforce it" — Jackson never said that, but only by a technicality!

Henry Clay had badly underestimated Jackson, a man he believed to be intellectually insignificant. Never had he expected an eight-thousand-word veto message that anticipated and demolished every possible objection! In addition to his Constitutional arguments, Jackson also imbued his veto message with an immense mass of populist rhetoric, attacking the bank on the grounds that it enfranchises a small number of rich, politically-connected men at the expense of everyone else; this was entirely novel in American history. Never before had a president used a veto in this manner; all seven of Jackson’s predecessors had used the veto only to enforce Constitutional limitations on acts of congress, and never to advance a particular political agenda. Clay hadn’t anticipated this tactic, and Jackson’s stunning and irrefutable claims suddenly positioned him on the side of the people, and Clay and the bank were the ones set up to take a beating. Riding the wave of popularity he gained from this message, Jackson indeed cruised to victory over Clay in the 1832 election, winning 219 electoral votes (of only 286 total). This unprecedented step by Jackson was the first major concentration of power in the president that would take place in American history — though, of course, it would be far from the last. Suddenly, the president was doing far more than "tak[ing] Care that the Laws be faithfully executed;" he was now standing in judgment over the Laws.

Jackson’s veto held up, and he was elected to a second term in office, but the bank’s existing charter was good for another four years, and Jackson (again, correctly) feared that Biddle and Clay would use the bank as a weapon against him, creating economic turmoil to be blamed on the president. To head off this potential attack, Jackson withdrew all federal deposits from the bank — a power not vested in the president, but in the secretary of the treasury. So dedicated was Jackson to his final offensive against the bank that he fired two treasury secretaries before he finally found one who would yield to his commands! Of course, all that money had to go somewhere, and Jackson (and his compliant new treasury secretary, Roger Taney) distributed the money to state-chartered banks (what his opponents would rightly tar as Jackson’s "pet banks"). These were, of course, also state-enforced monopolists no less than the Second Bank of the United States was; the primary difference is that their directors were loyal to the Democrats rather than the nascent Whigs. This also led to no end of economic trouble; Nicholas Biddle, Whig crony though he may have been, was a highly competent banker, and it must be said that the United States was maintained on solid economic footing throughout the period of the Second Bank. In contrast, many of the Democratic cronies Jackson replaced him with were much less disciplined and capable, and expanded credit at a vastly increased rate, causing widespread inflation, a problem that would only compound when Jackson issued his Specie Circular, requiring that buyers of government lands pay in specie, and not in bank notes. This led to a much greater demand for specie, and the collapse of a great number of the so-called "wildcat banks" that couldn’t meet the sudden spike in demand. Jackson is often let off the hook for this economic turmoil, since he was safely out of office before it really set in, but it was positively a reaction to his rather madcap fiscal policy. Note well that another consequence of Jackson’s careless handling of the nation’s finances is that, since people wrongly associate the crony wildcat banks with "free-market banking," the free market often takes the blame for what is clearly a massive failure of government policy.

Executive overreach and economic turmoil are bad, but we would be sorely remiss if we pretended that this was the worst of the Jackson-era policies. No, the worst thing president Jackson did was his horrible, inhuman Indian policy — a continuation, really, of his life’s work. Andrew Jackson was an Indian fighter for many years, and had long set about the task of, as Martin Van Buren described it, "the removal of the Indians from the vicinity of the white population, and their settlement beyond the Mississippi." As president, Jackson was stunningly effective at the task, succeeding before he left office in the elimination of all but a tiny, scattered handful of Indians from the United States. He spearheaded the passage of the ominously-titled Indian Removal Act of 1830, authorizing the president, at his sole discretion, to set aside land on the far side of the Mississippi river for the Indians, and then to relocate them to it. This relocation was initially packaged as voluntary — the president would urge the Indians to leave, and was authorized to pay them to leave — but, as with all "voluntary" government initiatives, the iron fist is buried inside the velvet glove, and Indians were forcibly relocated before long. This forced relocation is known today as the "Trail of Tears," and it was thoroughly disgusting; the Franklin Roosevelt administration is criticized quite harshly (as it should be) for its policy of relocating Japanese, German, Italian, and native Alaskan people to "internment camps," but at least those people were brought to the camps by train or by bus. The Indians relocated by the Jackson administration were forced to walk. Not only were they forced to walk, they were forced to walk an exceedingly long distance — in the case of the Cherokee, they were made to walk from their homes in Georgia all the way to Oklahoma, a trip of roughly a thousand miles. Many of them were forced to do so during the winter, when the climate was harsh and food was scarce. It’s estimated that four thousand Cherokee died from the journey alone.

Of course, Andrew Jackson was doing this all for their own good. As he phrased it:

Our conduct toward these people is deeply interesting to our national character. Their present condition, contrasted with what they once were, makes a most powerful appeal to our sympathies. Our ancestors found them the uncontrolled possessors of these vast regions. By persuasion and force they have been made to retire from river to river and from mountain to mountain, until some of the tribes have become extinct and others have left but remnants to preserve for a while their once terrible names. Surrounded by the whites with their arts of civilization, which by destroying the resources of the savage doom him to weakness and decay, the fate of the Mohegan, the Narragansett, and the Delaware is fast over-taking the Choctaw, the Cherokee, and the Creek. That this fate surely awaits them if they remain within the limits of the States does not admit of a doubt. Humanity and national honor demand that every effort should be made to avert so great a calamity.

Tremendous quantities of taxpayer money was spent with the direct goal of killing tens of thousands of Indians, and ripping the rest out of their homes and forcing them to endure a grueling, thousand-mile hike through the wilderness. Humanity and national honor demanded it.

One of the reasons Jackson won the presidency in 1828 was the so-called "Tariff of Abominations," a tariff bill signed into law earlier that year by president Adams, but which was actually sneakily concocted by Martin Van Buren and John C. Calhoun as a trap. The Democratic base consisted largely of southern farmers, and they were consistently harmed by the protectionist tariffs desired by the urban New England Republicans. Van Buren and Calhoun got a tariff bill of their own in play in 1828, though, which was specially designed to be unpalatable to the northerners; the idea was that the northerners would balk at the heavy duties it imposed upon northern industry, the southerners would vote against their own bill, and 1828 would pass with no tariff at all. The plan didn’t quite work out as desired, though; while New England and the south voted against the tariff as expected, the middle states messed everything up by voting overwhelmingly for it, and then John Quincy Adams, aware of the trap, refused to veto it.

Still and all, it was a trap that the Democrats could play both sides of, and Jackson ran against the tariff in 1828. One problem, though: once in office, Jackson didn’t appear to care much about the tariff, and nothing was done until the Tariff of 1832 (written, charmingly enough, by John Quincy Adams himself) lowered the average tariff rate, but shifted the burden back toward the south. This led to tremendous unrest in the south; it was impossible for the south to do anything legislatively about the tariffs (not a single congressman from the south had voted for the original protectionist Tariff of 1824, but it passed anyhow), and now it was shown that even getting their man in the White House didn’t accomplish anything. Many southerners, including vice president Calhoun, began to look for another solution, and they found it in the writings of Thomas Jefferson and James Madison: nullification.

Nullification (also called "interposition") is the act of a state government refusing to allow a federal law to be enforced within its borders, and was first elucidated in 1798 in the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions. The Virginia Resolutions state:

That this Assembly doth explicitly and peremptorily declare, that it views the powers of the federal government as resulting from the compact to which the states are parties, as limited by the plain sense and intention of the instrument constituting that compact, as no further valid than they are authorized by the grants enumerated in that compact; and that, in case of a deliberate, palpable, and dangerous exercise of other powers, not granted by the said compact, the states, who are parties thereto, have the right, and are in duty bound, to interpose, for arresting the progress of the evil, and for maintaining, within their respective limits, the authorities, rights and liberties, appertaining to them.

These resolutions were enacted in response to the Alien and Sedititon Acts of 1798, as the states of Virginia and Kentucky refused to recognize that the federal government had such powers. In 1832, they would be revived and used to deny the federal government the power to levy a protective tariff. "This right of interposition, thus solemnly asserted by the State of Virginia," vice president Calhoun said in his Fort Hill Address, "be it called what it may — State-right, veto, nullification, or by any other name — I conceive to be the fundamental principle of our system, resting on facts historically as certain as our revolution itself, and deductions as simple and demonstrative as that of any political, or moral truth whatever; and I firmly believe that on its recognition depend the stability and safety of our political institutions." Indeed, South Carolina held what was called a "Nullification Convention," overwhelmingly adopting an ordinance stating that the tariffs of 1828 and 1832 were in violation of the Constitution, and that, as of 1 February 1833, it would be unlawful to collect those tariffs in South Carolina. This precipitated what’s known as the Nullification Crisis.

President Jackson responded to this with his Proclamation Respecting the Nullifying Laws of South Carolina, declaring in no uncertain terms that he did not recognize any right of nullification or secession, and stating, in an unusually roundabout way, his willingness to use military force to collect the tariff:

An attempt by force of arms to destroy a government is an offense, by whatever means the constitutional compact may have been formed; and such government has the right, by the law of self-defense, to pass acts for punishing the offender, unless that right is modified, restrained, or resumed by the constitutional act. In our system, although it is modified in the case of treason, yet authority is expressly given to pass all laws necessary to carry its powers into effect, and under this grant provision has been made for punishing acts which obstruct the due administration of the laws.

Jackson’s leaps of logic here are quite severe — he’s gone from South Carolina making it illegal to collect a tariff to South Carolina attempting to destroy the United States government by force of arms without so much as a how-do-you-do, and has imputed with no substantiating argument a right of self-defense to government that would actually seem to work against him as much as it works in his favor — but his message is clear. Congress supported the president’s belligerence by passing the bluntly-named Force Bill of 1833, authorizing the president to use "such part of the land or naval forces, or militia of the United States, as may be deemed necessary" for the collecting of tariffs or for the enforcement of federal law. President Jackson also instructed senate Democrats not to negotiate with the nullifiers on a reduction of the tariff, clearly preferring to risk a civil war rather than compromise with people he had come to view as "the enemy." Fortunately, Calhoun was less pigheaded, and, finding little purchase with the Jacksonians, turned to Henry Clay’s Whigs instead, working out a compromise tariff that satisfied the South Carolinians. In this way, president Jackson was ultimately prevented from sending the military to enforce tariff collection, but he established a precedent that would pay horrible, bloody dividends only a few decades later, when another tyrant would seek to use military force to collect tariffs, and no cooler heads were able to defuse the situation.

If Jackson was militaristic domestically, he was peaceful abroad; he successfully settled outstanding spoilation claims dating from the Napoleonic Wars with France, Denmark, Portugal, and Spain, formed trade agreements with a variety of European countries, and opened the first American trade route to Asia. Jackson also made an attempt to acquire Texas from Mexico, but the attempt was a failure; unlike his protégé, James K. Polk, Jackson would actually refuse the suggestion that he invade and seize Texas through military power. President Jackson may have been a lifelong Indian fighter, but he seemed to have little taste for war with anyone else.

In retirement, Jackson remained active in politics, serving as a councilor and figurehead for the Democratic party for another eight years, until his death in 1845. Even today, he is regarded as the key figure in the history of the Democratic party; Martin Van Buren may be the man who created the party, but Andrew Jackson undeniably gave it life. Jackson perhaps was the first president to be truly larger-than-life, the first to rule by charisma and force of personality as much by law and Constitution. There is, unfortunately, danger in that, and most of the men who have emulated Jackson lacked his odd sense of restraint, and have used the precedents he set to do far more damage. The best laid plans of mice and men — and little magicians, it turns out — go oft awry.